A Tale of Two Victorian Crazy Quilts - in Four Parts

Parr 1

Setting the Scene

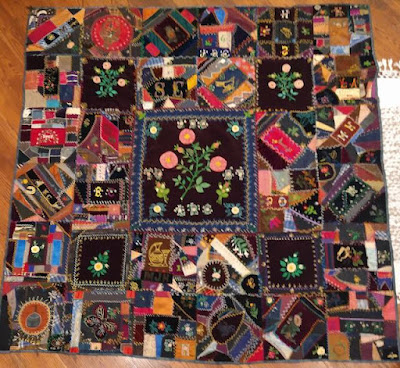

This pair of crazy quilts still lives in the family and the town where they were made, with a descendant of the two quiltmakers.

They were

made circa 1890 in Brooklyn, Connecticut, by Emily Harris, and her

daughter, Eva May Harris. They are great-grandmother and grandmother to

the current owner. One of the quilts has a small piece of red fabric

embroidered with the name of Samuel Cady Harris, Emily's husband.

Both quilts include bright yellow Special Constable ribbons and commemorative ribbons celebrating the dedication in 1888 of the statue of Gen. Israel Putnam. The town celebrates their native son as the third in command of the Revolutionary Army.

Some

of the fabrics were in pretty bad shape or missing altogether. I

patched those, mostly with vintage silks, though none are as old as the

original silks. Some others were still mostly in place but quite

shattered. I stabilized those with couching stitches so as to keep as

much as possible of the original fabric visible. Each quilt had one

patch that was pretty badly damaged but too interesting to patch over. I

covered those with crepeline, a very sheer silk, to protect them.

(Here's one, and the other is in the next photo.)

Here's a section that shows all the techniques that I used.

The plum arches over the fans were pretty well all torn. Here's one I patched.

A Tale of Two Victorian Crazy Quilts - in Four Parts

What's Going on Here?

But for me, beautiful and well-documented as these are, the project really got fun when I discovered what to me was an anomalous fabric and some curious earlier repairs.

Here's the area in question. There are three pieces where the silks have disintegrated to reveal a large piece of printed fabric, with colors that are light and loud compared to the rest of the quilt.

Here are the observations and questions that had me really scratching my head:

1.

The colors seemed out of step with what I'm used to seeing in quilts of

the late 19th century, particularly the bright, deep orange and the sky

blue.

2. My first sense of the fabric was that it felt more like what I remember of ladies' slinky, synthetic nightgowns of the 1960s. And the print style looked more like that era, too, not the 1890s.

3. Then I noticed the patches in that area have concentric embroidered edges, one along the shattered silks on top and one along the mystery fabric below them. And then I saw that the edge of the mystery fabric extended around several intact silk pieces as well. The entire area is about 10" x 13.5".

4. The mystery fabric was in much better shape than several of the silks that had been sewn on top of it.

5. I peeked inside the torn spots on the mystery fabric, and saw the same tan gingham that is used as a foundation fabric in other parts of the quilt. None of the torn spots were large enough to get a glimpse of a torn fabric that might have been lying between the mystery fabric and the foundation.

But what a mystery! Could someone have patched shattered 19th century silks with a large piece of synthetic 20th century fabric, and then, maybe someone else, re-patched that spot with some antique silks, some of which disintegrated pretty quickly??

6. That's a weird enough story, but consider this: the back and binding of the quilt are intact. So if the mystery fabric was mending a large tear or other disaster, it might be that all happened while it was a top, before layering and finishing.

Here's the completed patching over the mystery fabric area.

There's another place where a similar routine happened - a patch disintegrating faster than the original fabric beneath it.

And another piece where a painted fabric was apparently cut out and patched with a plain silk, which then disintegrated totally. So now all we end up seeing is the gingham foundation fabric.

A Tale of Two Victorian Crazy Quilts - in Four Parts

Science

So, we decided to try to identify the mystery fabric with a burn test.

Here's the set-up. There are some threads of the mystery fabric (removed with the owner's approval), seen just behind the candle. For comparison, I used swatches and threads of known fabrics of silk, rayon, and synthetics. Tools are a small candle, tweezers for holding samples, a fire-proof work surface.

I recorded the testing with my friend Pam Goffinet watching and helping me with the commentary. (I thought I could fix the exposure problems caused by the candle flame later, but found out I couldn't. I decided to pull some stills and fix them as best I could. Next time I do this, I'll be better prepared and hopefully get a better video... )

The

technique is to move a swatch slowly into the flame, and take note of

things like: how easily does it start to burn, does is burn quickly or

slowly, does it have an odor and what is it like, what kind of residue

is left when it goes out, and so on. There are lots of sites online

that give guidelines of what to look for on these kinds of topics.

I also tried a new technique I had recently read about - fiber testing with bleach. It seems that bleach destroys protein (animal) fiber and not cellulose (plant) fiber.

Here is a silk swatch on the left and a rayon swatch on the right.

Pretty quickly, things started to happen. It looks like color is coming out of both. What you're actually seeing on the silk (left) is a mass of teeny bubbles. Pam and I decided that was evidence of a chemical reaction between the silk and the bleach. What you see on the right is color loss, first turning blue and then losing that color as well, not a single bubble.

And finally, there's very disintegrated (and paler) silk on the left and a fully intact and basically strong rayon on the right.

And then came the actual testing of the fibers from the mystery fabric.

The results: Both burn and bleach tests are quite clear that the mystery fabric is silk, not an early synthetic or rayon.

The

fibers did not burn easily and once removed from the flame, went right

out. What you see hovering over the fibers here is smoke, not flame.

It had a dark ash, soft not hard.

The

silk fibers in bleach (next to tweezers in top photo, next to my finger

in next photo) did make tiny bubbles and then disappeared.

I

posted my questions on a couple of Facebook groups, and got an answer

from my friend Martha Spark, who said she's seen late 19th century

silks that have these colors. And then I finally remembered that silk

and wool, i.e. animal fibers, take dye much more easily than plant

fibers like cotton - and therefore a silk or a wool can often sport

colors that were more difficult to dye on cottons.

So all that means the patching could all have been done around the time the quilt was made.

But I still can't quite come up with a story I like - why was there such an light colored print put on such a large area of a generally dark set of fabrics, and then covered with fabrics similar to the rest of the quilt, some of which disintegrated faster than what they were patching? Maybe a temporary patch until better silks were found?

A Tale of Two Victorian Crazy Quilts - in Four Parts

Just Enjoy the Beauty

But anyway, mysterious mending aside, these quilts have loads of gorgeous and interesting fabrics and some fun embroidery.

I love these stripes. I can totally imagine a gorgeous gown made of either one. Statement outfits, for sure. I really like the more subdued brocade on the left as well. The gingham check is silk. Interestingly, the black has survived as well as the grey. The little squares between the check are nearly all gone - what you're seeing is a muslin underneath. Those little squares were originally white, as you can see at the top pointed corner where a few are still intact.

A rich, cut velvet stripe.

Here's a grouping of several tiny patches made from woven plaids and stripes. Exquisite!

A great embroidered rooster and also a shamrock stripe.

The

center fan block on this quilt has miniature fans in the corners. The

fans on these quilts are all notable for their very skinny spokes.

Hand painted flowers and a soft floral print, looking like watercolor painting.

One quilt is backed in this paisley, with a gentle woven ribbing. The other is backed with wavy lines.

.......And that's the end of the tale! The quilts are back home. The fabric mystery is solved, but the story line remains a mystery!